A company founded by millionaire Fouad Al-Zayat is asking the U.S. Supreme Court to help it secure a payment of about $8 billion on German bonds that Adolf Hitler ordered into default 78 years ago. Source: Random House via Bloomberg

A police officer stands in front of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. Photographer: Joshua Roberts/Bloomberg

A company founded by millionaire Fouad Al-Zayat is asking the U.S. Supreme Court to help it secure a payment of about $8 billion on German bonds that Adolf Hitler ordered into default 78 years ago.

Al-Zayat, 69, began buying the debt more than a decade ago in a bet that Germany is still on the hook for bonds issued near the end of the Weimar Republic, and that their value has soared because it’s tied to the price of gold. Mortimer Off Shore Services Ltd., a Nicosia, Cyprus-based company started by Al-Zayat and now run by his son and son-in-law, has spent millions of dollars on the investment and pursuing the claim in court, according to its attorney, Peder Garske.

“It’s not like they just happened to find these bonds in their attic or something like that,” said Garske, who declined to say how much the company spent acquiring the securities. “Through their contacts and through their own research, they concluded that these particular bonds were valid and considered by Germany to be valid and valuable. That’s why they acquired them.”

Jeffrey Harris, an attorney representing Germany in two cases filed by Mortimer Off Shore, said the company isn’t entitled to redeem the bonds. The government won a victory in the six-year legal battle in July when a federal appeals court in New York said the company didn’t follow procedures designed to screen out ineligible bonds, and that U.S. courts lacked jurisdiction over debt issued in territories that became part of East Germany after World War II.

Supreme Court Appeal

The Al-Zayat company in December asked the Supreme Court to intervene, arguing the lower court’s ruling had “enormous, negative ramifications” for holders of sovereign debt, because it means nations can renege on obligations entered into by earlier governments.

The Supreme Court plans to discuss the suit against Germany during a Feb. 18 private conference, according to its website. The high court may announce whether it will accept the case as soon as Feb. 22, its next scheduled day for issuing orders on pending matters.

“It’s a real long shot,” said Harris, an attorney at Rubin, Winston, Diercks, Harris & Cooke LLP in Washington. “The percentage of cases that get taken to start with by the Supreme Court is far less than 1 percent.”

Garske, of Baker & Hostetler LLP in Washington, said the case may appeal to the justices because it pertains to the rights of individuals and companies to sue foreign governments, an issue the high court has shown previous interest in. His clients sued in the U.S., not Germany, because they believed they were more likely to get a fair hearing, he said.

Gambling Debts

Syrian-born Al-Zayat made his fortune selling airplanes and oil in the Middle East. He became a favorite of the U.K.’s tabloid newspapers after refusing to pay a 2 million-pound ($3.2 million) casino debt 11 years ago that he accrued in a single night of gambling in London’s Mayfair district.

The casino, Aspinall’s Club Ltd., sued Al-Zayat in 2006. In subsequent court filings, it came to light that he had wagered 91.5 million pounds at Aspinall’s from 1994 through 2006, losing 23.2 million pounds. His gambling appetite prompted casino staff to refer to him as a “whale,” according to legal documents.

Justice Nigel Teare in 2008 cleared Al-Zayat of his unpaid losses, ruling Aspinall’s violated U.K. laws that prohibit casinos from extending credit to indebted gamblers.

“He admits that he fell into a trap of the well- established and experienced London casinos, who open their arms to indulge wealthy people to live the high-roller lifestyle,” according to a statement on Al-Zayat’s website. “It is a lifestyle and addiction that he deeply regrets.”

Al-Zayat, who is retired, didn’t respond to an e-mail seeking comment.

Gold Clause

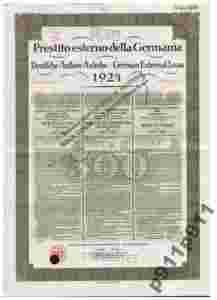

While he gambled at London casinos, Al-Zayat was also investing in debt German banks issued in 1928 to improve the nation’s agricultural conditions after World War I.

Al-Zayat started purchasing the bonds in the 1990s through Mortimer Off Shore, which he set up to make investments, Garske said. His son and son-in-law continued to buy the debt after they took control of the company, Garske said.

The 30-year bonds were first sold in $1,000 increments in the U.S. and paid annual interest of 6.5 percent twice a year. To attract buyers, the debt included a clause that specified lenders could demand repayment in dollars equivalent to the value of gold. Gold sold for $20.66 an ounce on average in 1928, according to the Washington-based National Mining Association.

$5 Million Each

Mortimer Off Shore’s attorneys calculate that each $1,000 bond represents about 3,663.25 troy ounces of gold. When multiplied by the metal’s current price of about $1,365 an ounce, the firm estimates each of the 1,611 bonds held by the company, including unpaid interest and principal, is worth $5 million, or a total of $8 billion.

The company combined its holdings with an investor who owns 83 bonds in a separate lawsuit brought against Germany in September. The suit, filed in Boston, says Mortimer Off Shore has obtained additional evidence that shows Germany agreed to guarantee the bonds and that the nation’s total liability exceeds “$7 billion and continues to increase.”

The claims aren’t valid because Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court forbade gold clauses in the 1930s amid concerns that demands for the metal risked exhausting the U.S. Federal Reserve’s supply, said Harris, Germany’s lawyer.

Lawmakers decided in the 1970s to reinstitute gold clauses, but only in contracts entered into after 1977, he said. Even if Mortimer Off Shore had a valid claim, the bonds are valued at about $3,400 each based on Germany’s calculations, or a total of $5.48 million, Harris said.

Orphans, Widows

Garske said he disputes Harris’s interpretation of U.S. laws governing gold clauses, and whether the ban on them ever applied to foreign debtors, such as Germany.

Bob Kerstein, who owns a Fairfax, Virginia-based business that sells historical bonds as collectors’ items, said he gets phone calls all the time from speculators. Scam artists also try to market old bonds to “orphans and widows,” citing gold clauses as a pathway to riches, he said.

“For somebody to buy these bonds and think they are going to make millions and millions of dollars, I think it’s an uphill battle,” said Kerstein, chief executive officer of Scripophily.com in Chantilly, Virginia. “The first step is winning in the courts, and even if you do, you may not collect the money. I’m not sure it’s worth speculating on.”

The bonds Al-Zayat and his family bought went into default when Hitler came to power in 1933. A portion of the bonds were then repurchased by issuers, invalidated and stored in bank vaults, according to German officials.

Repurchase Process

After World War II, territories that became West Germany agreed to honor the debt if lenders agreed to let officials review the bonds to determine that they hadn’t already been repurchased. Germany set up the validation procedures after claiming Russian soldiers had looted numerous already-redeemed bonds from banks and re-circulated them into the market when Germany surrendered to Allied forces in 1945.

Mortimer Off Shore contends in its Boston lawsuit that the validation procedures are “nothing more than a mechanism to deny legitimate claims.”

The firm also said bondholders aren’t required to validate their debt. Rather, validation was a legal process that was set up to ensure “expeditious payment,” according to the suit. Mortimer Off Shore can’t validate its bonds even if the company wanted to, because the procedures to do so no longer exist, and never applied to territories that became East Germany, Garske said.

World Holdings Case

Some of the banks that issued the bonds were located in what became East Germany after the war.

Germany is trying to fend off a similar lawsuits, including one filed by World Holdings LLC, a Tampa, Florida-based company that controls “a significant number” of bonds issued in 1924 and 1930. The case is pending after a U.S. appeals court in Atlanta rejected Germany’s request to dismiss the suit in August.

Harris, who also represents Germany against World Holdings, said he understands why investors have speculated on bonds issued decades ago.

“There’s the allure, and at least the hope, of a huge payday with comparatively very little investment,” he said. “That’s the great American dream.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Jesse Westbrook in London at [zasłonięte]@bloomberg.net.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Christian Baumgaertel at [zasłonięte]@bloomberg.net