|

KONTAKT:

telefoniczny:

Kom. 506 [zasłonięte] 408

e-mail:

danusia_[zasłonięte]@tlen.pl

GG: [zasłonięte]49632

>>>Zadaj pytanie

ZASADY DOSTAWY:

1.Szybko i bezpiecznie! Wszystkie przesyłki wysyłam jako polecone priorytetowe - zabezpieczone w kopercie bąbelkowej lub w przypadku większej ilości książek w paczce.

2.Przy zakupie większej ilości książek na moich aukcjach , proszę o kontakt a ja zważę książki i podam koszt wysyłki.

3. Wysyłka za granicę Polski według cennika Poczty Polskiej.

4. W cenę przesyłki wliczone są koszty opakowania.

5. Wysyłki zakupionych produktów robię codziennie między godziną 14 a 15 . Przesyłek nie nadaję sobotę, niedzielę i w święta kiedy poczta jest nieczynna.

6. towar wysyłam za pośrednictwem

INNE INFORMACJE:

1. Z mojej strony mogą liczyć Państwo na rzetelną i fachową obsługę oraz szybką wysyłkę zakupionego produktu.

2.Informuję każdego kupującego z osobna mailem o wysyłce towaru

3. Dla przyspieszenia wysyłki zakupionego produktu zachęcam do płatności za zakupiony produkt poprzez opcję '' PŁACĘ Z ALLEGRO ''

4. Numery kont :

- mBank

- PKO Inteligo

zostaną podane w mailu z Allegro, oraz znajdują się na stronie '' O Mnie ''

5. W tytule przelewu proszę podać nick z Allegro.

6. Jeśli adres do wysyłki ma być inny niż ten podany na allegro to proszę o jak najszybszą informację po zakupie.

7. Na wpłatę czekam 14 dni, potem rozpoczynam procedurę zwrotu prowizji i wystawiam negatywny komentarz

8. Moją ofertę możesz połączyć z innym allegrowym nickiem, koszt wysyłki będzie jeden

wielki200

|

|

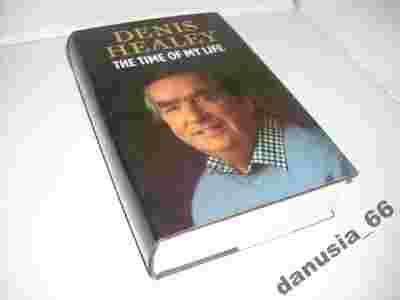

OFERUJĘ UŻYWANĄ KSIĄŻKĘ, ZDJĘCIE KSIĄŻKI REALNE

|

TYTUŁ KSIĄŻKI : '' THE TIME OF MY LIFE ''

AUTOR :DENIS HEALEY

ILOŚĆ STRON : 606

OPRAWA : TWARDA Z OBWOLUTĄ

STAN OGÓLNY KSIĄŻKI : BARDZO DOBRY MINUS, OBWOLUTA TROCHĘ PODNISZCZONA, BRZEGI KARTEK LEKKO PRZYBRUDZONE

OPIS TREŚCI : In his autobiography Denis Healey does not pause to ponder whether, as in the opinion of so many, he is the greatest prime minister Britain never had. But he holds in low regard almost all of those who held the office during his own time in Parliament. Of the leaders whom Healey himself served, the woolly, short-termist Wilson is held in contempt, although Callaghan is admired both for his management of the cabinet and for his integrity: "once prime minister, he had no ambition except to serve his country well".

And evidently one of Callaghan's great services to his country was to retain Healey as his Chancellor - a role in which Callaghan himself had failed a decade earlier. The chapters dealing with Healey's labours at the Treasury are at the heart of the book. He figures himself as Hercules cleaning the Augean stables, as he restores stability to the UK economy after Tony Barber's calamitous superintendence of it under Heath. Healey arrived the Treasury in 1974 with no grounding in economics, as he admits, and therefore with an open mind - sceptical in economic theory, as in ideology, of all dogma. But he is a layman with a truly giant intellect, and the book is at its most illuminating as he applies his voracious mind to the evils conjured up by Barber's credit boom and by OPEC's trebling of the world oil price in 1973.

A layman in economics, Healey's political training had been in international affairs and defence. The book was written in 1989, unknowingly on the very eve of the revolutions in eastern Europe, and its long treatises on nuclear strategy appear today somewhat dated. But as the book's title suggests, Healey applied his talents within the paradigm of his own age, and by so doing distinguished himself from other clever men of his generation - such as Enoch Powell, Tony Benn, and Michael Foot - whose response to the same challenges was to attach themselves to romantic ideals of one sort or another. Healey is a romantic, but never an eccentric.

Well-known is his devotion to his "hinterland" of art and literature, music, travel, and photography. His passion for culture has informed every passage of his long life, and the book evokes it well. Healey himself wonders whether his failure to capture the premiership was attributable to a trimming of his ambition in the knowledge that there is more to life than politics. That may be. Another factor, which Healey does not discuss, might be the use that he made of the war years, serving with distinction and valour on the beaches of Anzio whilst the future Labour leaders, Gaitskell and Wilson, were learning the ways of Whitehall as temporary civil servants.

Yet another factor, suggested by Edward Pierce in his essay on Healey in The Lost Leaders, is the arrogance which set Healey apart from his fellow Labour MPs, and which encouraged them in 1976 to prefer as Wilson's successor the homely trade unionist Callaghan to the aloof Balliol alumni Healey and Jenkins. Certainly Healey's prose, although not as fluent as Jenkins', is charged with a similar pomposity: the highest accolade that Healey can bestow on one of his fellow men - and he bestows it on many - is that he is "brilliant".

The book makes plain why Healey wished to enter politics - politicized during the 1930s, a witness at first hand of pre-1939 Nazi Germany, he sought to combat totalitarianism and to contribute to peace. Less clear is why he joined the Communist Party as a youth, or, for that matter, why he settled later with Labour. His contemporary Ted Heath had much the same political education but chose differently, and there is nothing from Healey of the kind of indignation at the other abiding image of the Thirties - the Depression - that might have pushed a Yorkshire grammar-school boy into the arms of the Left. On questions of social justice, Healey is silent; nor does he disclose any view on religion. This is a pity. The book's main flaw is that it affords no glimpse of the moral underpinning of Healey's politics. Without that, we have no counterpoint to Jenkins' view of his rival - that he carried only light ideological baggage on the heaviest of gun-carriages.

|

|

* ZDJĘCIE STANU KSIĄŻKI *

|

Staram się opisać stan książki bardzo dokładnie, jednak książka może mieć ukryte wady, których nie zauważyłam. Jeśli takie są to przepraszam. stan książki tak, jak na realnym zdjęciu widać. Książka kilka lat już ma, więc proszę przyjąć ze zrozumieniem ewentualne otarcia na brzegach, pożółkłe kartki, nieznaczne przybrudzenia czy zagięcia. Są to przecież usterki typowe dla niemal każdej książki używanej ... wieloletniej bardziej niedoskonałości widoczne ( np. luźne kartki, ubytki, Bardziej widoczne przybrudzenia) opisuje. KSIĄŻKI SĄ PRZECHOWYWANE NA REGAŁACH, WIEC NIEKTÓRE Z NICH MOGĄ BYĆ ZAKURZONE

| | |