|

Thirty years ago, two young biologists named Robert

MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson triggered a far-reaching

scientific revolution. In a book titled The Theory of

Island Biogeography, they presented a new view of a

little-understood matter: the geographical patterns in

which animal and plant species occur. Why do marsupials

exist in Australia and South America, but not in Africa?

Why do tigers exist in Asia, but not in New Guinea?

Influenced by MacArthur and Wilson's book, an entire

generation of ecologists has recognized that island

biogeography - the study of the distribution of species

on islands and islandlike patches of landscape - yields

important insights into the origin and extinction of

species everywhere. The new mode of thought focuses

particularly on a single question: Why have island

ecosystems always suffered such high rates of

extinction? In our own age, with all the world's

landscapes, from Tasmania to the Amazon to Yellowstone,

now being carved into islandlike fragments by human

activity, the implications of island biogeography are

more urgent than ever. Until now, this scientific

revolution has remained unknown to the general public.

But over the past eight years, David Quammen has

followed its threads on a globe-circling journey of

discovery. In Madagascar, he has considered the meaning

of tenrecs, a group of strange, prickly mammals native

to that island. On the island of Guam, he has confronted

a pestilential explosion of snakes and spiders. In these

and other places, he has prowled through wild terrain

with extraordinary scientists who study unusual beasts.

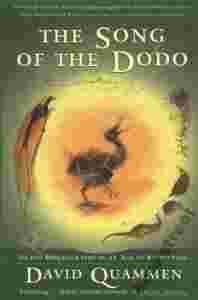

The result is The Song of the Dodo, a book filled with

landscape, wonder, and ideas. Besides being a

grandoutdoor adventure, it is, above all, a wake-up call

to the age of extinctions. |

|