|

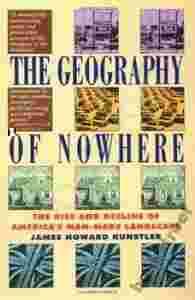

Eighty percent of everything ever built in America

has been built since the end of World War II. This

tragic landscape of highway strips, parking lots,

housing tracts, mega-malls, junked cities, and ravaged

countryside is not simply an expression of our economic

predicament, but in large part a cause. It is the

everyday environment where most Americans live and work,

and it represents a gathering calamity whose effects we

have hardly begun to measure. In The Geography of

Nowhere, James Howard Kunstler traces America's

evolution from a nation of Main Streets and coherent

communities to a land where everyplace is like noplace

in particular, where the city is a dead zone and the

countryside a wasteland of cars and blacktop. Now that

the great suburban build-out is over, Kunstler argues,

we are stuck with the consequences: a national living

arrangement that destroys civic life while imposing

enormous social costs and economic burdens. Kunstler

explains how our present zoning laws impoverish the life

of our communities, and how all our efforts to make

automobiles happy have resulted in making human beings

miserable. He shows how common building regulations have

led to a crisis in affordable housing, and why street

crime is directly related to our traditional disregard

for the public realm. Kunstler takes the reader on a

historical journey to understand how Americans came to

view their landscape as a commodity for exploitation

rather than a social resource. He explains why our towns

and cities came to be wounded by the abstract dogmas of

Modernism, and reveals the paradox of a people who yearn

for places worthy of their affection, yet bend their

efforts in an economic enterprise ofdestruction that

degrades and defaces what they most deeply desire.

Kunstler proposes sensible remedies for this American

crisis of landscape and townscape: a return to sound

principles of planning and the lost art of good

place-making, an end to the tyranny of compulsive

commuting, the un |

|