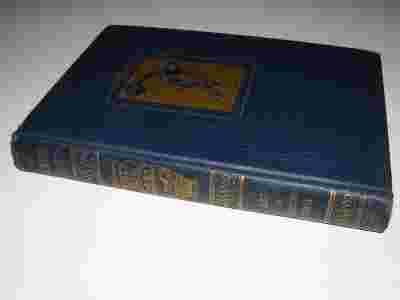

SZTUKA CZASY STAROŻYTNE PREHISTORIA EGIPT... 1940

Aukcja w czasie sprawdzania nie była zakończona.

Aktualna cena: 49.99 zł

Użytkownik inkastelacja

numer aukcji: 2442797967

Miejscowość Kraków

Wyświetleń: 17

Koniec: 03-07-2012 19:46:47