Richard Fortey retired from his position as senior palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum in 2006. He is the author of several books, including 'Fossils: A Key to the Past', 'The Hidden Landscape' which won The Natural World Book of the Year in 1993, 'Life: An Unauthorised Biography', 'Trilobite!' and 'The Earth: An Intimate History' and Dry Store-room No. 1. He was elected President of the Geological Society of London for its bicentennial year of 2007, and is a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Survivors by Richard Fortey: review

A passionate exploration of the flora and fauna that have stood the test of time

30 Aug 2011

Richard Fortey accumulated lots of air miles and generated a veritable hecatomb of unfinished in-flight meals while writing this book (and as an employee of the Natural History Museum that means economy class cuisine). He visited New Zealand, Alaska and other US states, Ecuador, Hong Kong, Lithuania, Newfoundland (where, off Mistaken Point, the “bones of 50 ships lie offshore, waiting to be fossilised”), Australia, Malaysia, Majorca, Singapore, Germany, Portugal, mainland China, Spitsbergen and even south Wales (where, when we eat laver bread with its primitive seaweed ingredient, we “munch at a Pre-Cambrian trough”).

Everywhere, Fortey is searching for the remnants of days long gone. Fortey does not like the term “living fossil” (although both he and I, fortunate in having spent careers pursuing apparently irrelevant facts about obscure animals, would fit that description in today’s academic world). Instead he goes for those few members of ancient groups that have persisted to the present day.

Survivors is an exploration of the world that went before. Fortey retains his characteristic ability to paint vivid word-pictures of times long ago and places far away. The book begins with a trip to the shores of Delaware, where, once a year, thousands of horseshoe crabs, scarcely changed for more than 100 million years, indulge in group sex. As they heave their way onwards, like battered tanks, Fortey gets the clear message: “Survival is all”. He has spent most of his life studying trilobites, a related group of marine jointed-limb creatures which died off with the dinosaurs, so for him the trip to the horseshoe crabs of Delaware was like a Catholic’s first visit to the holy city of Rome: a breath of life amid a career otherwise preoccupied with death.

In the old days, history used to be about chaps, geography about maps and the fossil record mainly about gaps. Now, many of those gaps are being filled in – by fossils, but also by the variety of creatures that creep shyly onto these pages. They are, of course, not our ancestors, but they remind us what our ancestors might have been. They include the velvet worms, whose antecedents date back almost unchanged to the Cambrian era. They are reminders of the earliest days of segmented animals, which include crabs, insects and earthworms. At the other end of the scale is the hellbender, a giant salamander of American streams and, in the vegetable world, the Gingko tree – which, although now a familiar inhabitant of London streets, has leaves that have scarcely changed for almost 300 million years.

In the genetic sense, of course, we are all survivors. Just this week there was a report of cell-like structures from almost three and a half billion years ago – a time when the ocean had the temperature of a hot bath, the air was full of methane, and the moon loomed enormous in the skies – from some beds in Australia. They may be the oldest fossils of all – and, although they did not last, almost every living creature on Earth is their descendant.

Related Articles

Most of the heroes of Fortey’s pages have stuck to what they like by adopting an obscure and specialised way of life. Many are unfamiliar to non-biologists, and deserve their 15 minutes of fame. As Fortey says, names really matter, but there are perhaps too many here for the average reader. On the way through the evolutionary forests of the almost forgotten we read plenty of Latin, for Fortey does not hesitate to use technical names of plants and animals. He also admits that he does not like just to take the evolutionary trip from A to Z, or even from Z back to A and instead hops alarmingly back and forth through the eras until the incautious reader might be left gasping to discover quite which geological stratum he is in.

Fortey suggests that to retain as much as we can of the remnants of early life, certain parts of the world might be designated as “time haven” reserves. They include the shores of Hong Kong, the submarine Queensland Plateau off the east coast of Australia, New Caledonia, and the Huangshan mountains of China, each of which shelters many refugees from the unimaginably distant past and each of which deserves special care if our own descendants are to experience those ancient voices before they are finally stilled.

The book is passionate, clear and comprehensive but says oddly little about the greatest living fossil of all: man himself, whose physical appearance has scarcely changed since he first appeared on Earth, but whose mental – and physical – universe has been transformed, even within the past millennium. We ourselves have adapted to so many changes that the whole globe has become a nature reserve, a time haven, for Homo sapiens. We will, perhaps, end up as the biggest survivor of all as we adapt in the future – as we have so often in the past – to challenges such as climate change, disease and food shortage.

And to remind the many who think that studying obscure remnants of the past (even on economy class) is a waste of taxpayers’ money, a component of horseshoe crab blood is now widely used in medical tests to detect minute quantities of bacterial poisons; a discovery, ironically, that put the survival of the crabs themselves at risk as they were pillaged for pharmaceuticals. They have now been saved, as a reminder that science – like much of this book – is the art of the unexpected.

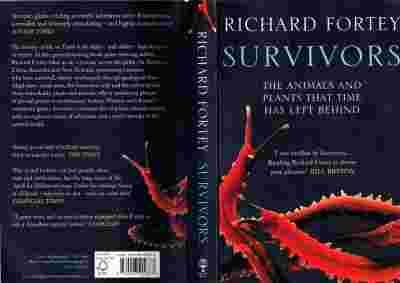

Survivors: The Animals and Plants That Time Has Left Behind

By Richard Fortey

336pp, Harper Press, £25

Survivors by Richard Fortey - review

A search for some of the planet's most ancient life forms

Biology is the most complex of all the sciences and the one that touches us most closely; and natural history is half of it, simply observing what is, what's out there, and what it all does. Good naturalists are humble – properly awed by nature and always aware that life in the end is beyond our understanding. But the other, more practical half of biology – biotechnology, genetic engineering and all that – is flashier and more lucrative and so attracts all the funding. The humility is gone. The biotechnologists tend to assume that we already know all that's worth knowing; that we can take nature by the scruff and reshape our fellow creatures at whim, just by fiddling with their DNA. The Greeks were right about hubris. We need to restore the balance. Bring back natural history.

This is Richard Fortey's great strength. He is known as a palaeontologist, a scholar of fossils, but he is, he tells us, "a naturalist first". His latest book is in the great tradition of natural history – that of the nature ramble, led by the authoritative and other-worldly sage. He leads us on a ramble that is not only global but takes us through aeons, to look at creatures that haven't changed much to look at for hundreds of millions and in some cases for billions of years. Worldwide, there's a surprising number of these ancient types: it's a mistake to assume that the creatures that evolved later necessarily supplanted the ones that came before. Nature often arrived at very good solutions to life's problems a very long time ago – and why change a winning formula? Natural selection may work just as efficiently to keep things the same as it so obviously does to change them.

Take limulus – the horseshoe crab of North America, with an armoured carapace and jointed, arthropod legs, that scuttles on the sea bed like a clockwork toy: it's not in truth a crab at all but a very primitive arachnid, relative of the spiders and scorpions. It is very ancient indeed – fossils very similar are known from the Ordovician, 450m years ago; they clearly arose in the Cambrian, at least 500m years ago. For hundreds of millions of years they shared the seas with the trilobites, which were superficially similar and perhaps were distantly related. The trilobites were far more numerous than the early horseshoes, and far more varied: some of them predatory, some of them squeezing the nutrients from mud, and some of them free-swimming. But, as the fossils clearly show, the trilobites went extinct as most animals did in the greatest of all mass extinctions at the end of the Permian, around 255m years ago.

But the humbler horseshoes came through. Conditions deep down stay constant when turbulence reigns overhead. So life may favour the ultra-conservative. But horseshoes have other tricks, too. They can survive tremendous damage, largely because their blood clots so efficiently, sealing all wounds, and because they have a supremely effective immune system.

On the east coast of North America an estimated 17m horseshoes still come ashore each year to lay their eggs in the sand, like turtles. But whereas female turtles mate at sea and come ashore to lay eggs that are already fertilised, horseshoes lay infertile eggs. So the males come ashore too and compete to fertilise the eggs as they are laid. Fortey describes all this first-hand, in Delaware Bay, the greatest of all horseshoe breeding grounds; and if he had lived 400m years ago the spectacle would have been much the same. Seabirds come too. For them the horseshoe eggs are an essential feast, a staging post on their vast migrations from the deepest south to the Arctic.

The ramble continues: to New Zealand in search of the velvet worm,onychophora. On the west coast of Australia he encounters thestromatolites, built from layers of minerals and photosynthetic bacteria (bacteria invented photosynthesis, and plants nicked it from them). They're still going strong though they date from around 3,000m years ago. In North America's Grand Teton national park Fortey gets to grips with microbes that live in the super-heated water of the hot springs; possibly the conditions in which earthly life began. He likes plants, too, and meets clubmosses, whose ancient relatives were huge and abundant forest trees; tree ferns; and ginkgo biloba, sole survivor of the once huge and various tribe of the ginkgoales. And many more.

All in all it's a great story, and no one is better equipped to tell it than Fortey. Just one cavil: though evolution is well established as a fact of life (as much as any historical science can be), there are still some metaphysical loose ends that can never be put to rest but could certainly be addressed through a survey such as this. Is there progress in evolution? Can we really suggest that sophisticated creatures such as orb-web spiders – modern arachnids – have "progressed" since horseshoe days? What does progress amount to, if the ancient types are still thriving? What of the old concept of orthogenesis – the idea that evolution proceeds in straight(ish) lines from a primitive state to modern types? What do we make of "convergence" – while nature is endlessly inventive, why does it endlessly reinvent the same general forms and life-solutions in remarkably similar forms, such as the predilection for flat, armoured creatures, including trilobites and horseshoes? Where does this apparent sense of direction come from?

But Survivors is excellent natural history, even so. And, as those who finance science need reminding, natural history matters.