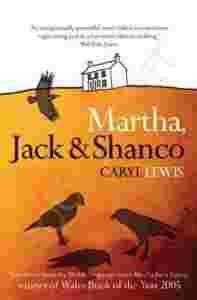

|

A tight, close-up little drama with rural

characters, including slow Sianco who keeps his terrier

under his jumper at all times . Their farmhouse is

Graig-ddu ( Black Rock ); The orchard came right up

behind the house, making it dark and damp; the wallpaper

s original light blue a distant memory, since by now it

was blackened by smoke. , no rural idyll but Lewis eye

for detail gives us pleasure amidst the squalor and

unpleasantness (as those who romanticise rural existence

might see it). Her eye is an eye for humour too; As she

put the teapot on the table, Jack pulled off his hat and

gave it to the pot to wear while it brewed the tea .

Staccato chapters envision the repetitive uncomfortable

moments of these isolated farming siblings life, frying

bacon and potatoes, slaughtering turkeys or training

sheepdogs. But there is a drama unfolding here about

marriage and property as in the best Jane Austen. One

commentator (Diarmuid Johnson) sees the story of the

three siblings in their hillside farm as a metaphor for

the whole Welsh-speaking rural life under threat from

both socio-economic change and cultural and linguistic

encroachment from English-speakers. If this is the case

then the tragedy it outlines is of a population

marginalised by the very isolation (and poverty) that

has enabled it to preserve the Welsh language. Visiting

the churchyard to lay a Christmas wreath on Mami s

grave, Martha the daughter of the family notes There

were never any flowers except her flowers on the graves:

the three of them were the only family left. And of the

three, poor old Shanco is slow-witted and dependent,

Jack is a miser, lured by the pragmatic glamour of the

English-speaking midlander Judy who would transform

Graig-ddu into an acculturated dude ranch. Martha is the

only one as tradition or rather memory-bearer of her

clan in a position to combat elder brother Jac s

nihilistic vision: There s nothing here, Martha. It s

all finished. We re all finished. The story of this long

slow retreat of an old way on the Welsh hills is

expressed in the poignancy of Martha s patrilocal

dilemma: if she marries her patient admirer Gwynfor she

must move from the old farmstead, leave it to Jack and

Judy and Judy s wasteful horses and crass

petty-bourgeois Anglo ways. Lewis masterfully builds up

a sense of foreboding in this tight family scenario, of

irreconcilable, deep-seated long-lived conflict. We only

sense that something must happen, that some spark will

detonate the gunpowder. Less obviously there are

mysterious elements in the narrative huge threatening

crows for one that provide an essential depth, the space

for the unresolved and unknown that real writing needs.

Inter alia there is plenty about animals here too,

including an amusing account of a sheepdog s intense

jealousy and protectiveness for his master; Glen would

also walk between Jack and Gwen.... When they started

going out, Glen would bark at her and refuse to settle

until she was on her way. After six months or so the dog

would let them hold hands but he would walk between them

under their clasped hands. He would also sit between

them on the settle. All in all a graphic and

beautifully-described portrayal of farm life and place,

a real confrontation with a particular kind of

existence.

|

|